In discussions about humanity’s impact on the planet, conversations invariably turn to our treatment of the world’s rainforests. We continue to cut down large swathes of forest every year, with an area almost the size of South Africa lost since 1990, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization.

Activities such as illegal logging, deforestation to create farmland, and domestic heating and cooking suggest timber use will always be synonymous with ecological degradation. But to label wood use as unsustainable does the material a great disservice.

Timber is in fact a versatile, easy to use (and reuse) aesthetically pleasing natural product which, if trees felled are replaced and forests and woodlands carefully managed, should not run out.

If trees are replaced and forests and woodlands carefully managed, timber shouldn’t run out

In fact, with new wood technology, timber is as strong, durable and fire-resistant as steel. And that is not all. Substituting a cubic metre of wood for other construction materials, like concrete, blocks or bricks, results in a 0.75–1 tonne CO2 saving, storing carbon, unlike manmade materials that require huge amounts of fossil fuels and harmful emissions to produce.

Meanwhile, as a report from the Timber Development Association in Australia shows, timber buildings are 10–15 per cent more cost effective than other materials across many building types.

It’s no surprise, then, that consumers are increasingly preferring timber-framed buildings, which now account for 70 per cent of all new houses built around the world today. And advances in technology mean timber will increasingly be shaping the skyline, with taller and bigger timber buildings built, planned or in development around the world.

A wooden renaissance

Wood is certainly enjoying a renaissance, driven in part by consumer and regulatory demands to cut the use of plastics and find sustainable alternatives. Many traditional wood fibre companies, such as paper and wood product manufacturers, are investing in research and development. This is because only those which can adapt their business models can find innovative solutions to tackle health and environmental challenges and boost profits.

Austria’s Lenzing is one of several innovating firms. It manufactures textile fibres from refined wood pulp including viscose, tencell and other technology that can be found in everything from gym outfits to firemen’s suits. South African paper company, Sappi has started producing “dissolving wood pulp” – an important input material for viscose production.

Substituting a cubic metre of wood for other construction materials results in a 0.75–1 tonne CO2 saving

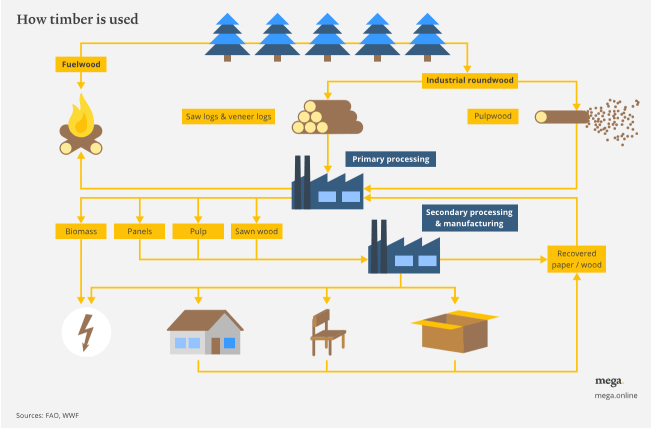

The resurrection of wood in modern life means investing in timber is not just about owning pure timberland. Since wood is versatile, it allows us to invest across the timber value chain, which include products such as container board, paper, pulp, packaging and hygiene as well as operators such as homebuilders.

The timber industry is at a tipping point. While timberland values remain low, supply is tightening

up, not least because of sawmill closures at the end of 2018.

The mountain pine beetle has destroyed at least 13 million hectares of pine forests in Canada’s British Columbia, while tariffs on imported Canadian softwood lumber and increasing wild fires in parts of Canada and the US are weighing on supply. China’s ban on logging its own forests and import restriction on recovered paper aggravate the country’s already large wood fibre shortage.

Meeting supply challenges sustainably

On the other hand, demand is rising against the backdrop of rising income in emerging economies and shrinking water and arable land resources. Take wood-based fibre for example – the industry is expected to grow 5-6 per cent every year between 2017-2022, outpacing the total fibre market which will likely expand by 3-4 per cent.

Taking all of this into account, timber offers a compelling case. Valuations of some of the promising timber companies look too cheap in the public market to be justified by fundamentals.

It may only be a matter of time before timber becomes ubiquitous – be it your clothes, the ingredients in your mid-afternoon snack, the packaging of your milk, or the buildings you live and work in, so much can be made of wood.

Chistoph Butz is the Fund Manager of the Pictet Timber Fund

This article is taken from the Good Investment Review Spring 2019, your guide to the best sustainable investment funds available to UK investors today. Download your FREE copy today!