The world is not, arguably, in the best political shape. Here in the UK Ministers of Parliament are currently waging a fierce internal war the likes of which has not been seen for decades, if perhaps centuries as legal challenges seem to mount by the hour against Prime Minister Boris Johnson.

The picture in Europe isn’t rosy, either. German Chancellor Angela Merkel, once referred to as ‘Grandmother Merkel’, has been forced to resign leadership of her party over public dissatisfaction with her party’s immigration policy, while in France centrist President Macron continues to struggle to contain so-called Gilet Jaune protesters, who since October 2018 have been storming the streets of Paris every weekend to express their displeasure over the current state of affairs.

Meanwhile, across the Pond the self-proclaimed home of freedom and democracy is – these days – looking a little less free, and a lot less Democratic.

So what does any of this have to do with money? Everything. Just as in the mid 1930’s – the last time we saw this level of political unrest across the Western world – this has EVERYTHING to do with money. Last week we reported on Oxfam’s latest inequality report, which contained one striking chart that neatly explains all we see happening in the world today.

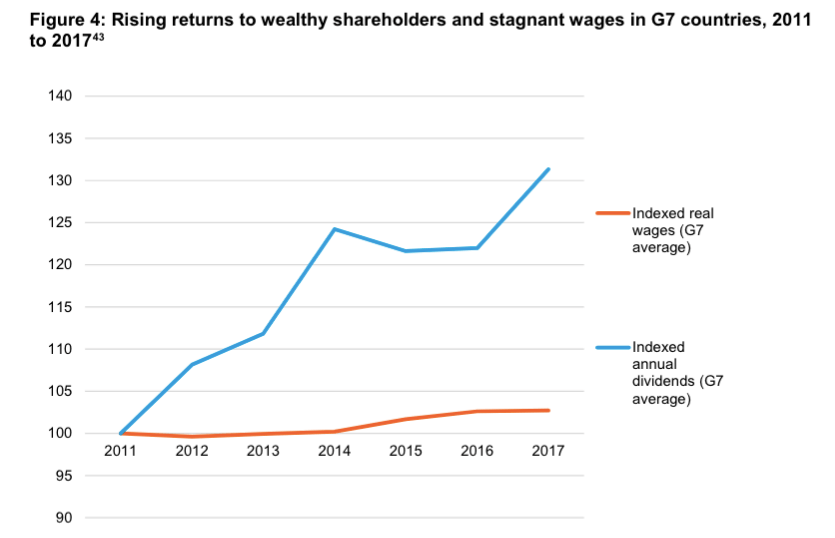

Here it is again:

What this chart shows, is that between 2011 (two years after the start of the worst financial crisis since the Wall Street crash of 1929) and 2017, average wages in the richest seven countries in the world grew by less than 3 per cent, while dividends to shareholders grew by 31 per cent.

And this is because in 2009, in order to bail out the world’s banks that had been recklessly lending and gambling with customers’ money since the liberalisation of financial markets in the 1980’s (cheers, Maggie), governments all over the globe had to issue vast sums of debt to print vast sums of money to keep them, and global markets, afloat.

As the chart above shows, this has meant a boom time for investors. However, the flip side of money printing (or Quantitative Easing) is that it keeps both inflation and interest rates low. Low inflation means low wages, while low interest rates means cash savers – who used to be able to rely on average annual returns of 5 per cent – haven’t seen rates move above 1 per cent since the Bank of England slashed rates in 2009.

Meanwhile, while inflation has been low by historic standards and has held down wages, it has still been running higher that interest rates, meaning these cash savers have in-fact been losing money in real terms.

This has heavily affected pensions, as annuities (the type of pension every retiree except rich ones relied on before the crisis) use the base interest rate to calculate returns. This is why George Osborne allowed pensioners broader access to their pension pots in 2015, knowing full-well that interest rates weren’t going anywhere anytime soon.

Rich and poor

In short, the measures that Western governments took to avoid economic collapse in 2009 have made the average Joanne poorer, while rich investors have got much, much richer. And now, ten years on, these chickens are coming home to roost.

All across the world average workers are angry, and they are angry because they are poorer. As is ever the case, the wealthy and powerful have done their best to deflect blame toward immigrants and ethnic minorities and – again as ever – they have had some success.

The fact remains, though, that poor people are poor, and as the Oxfam report outlines, they are poor because of an economic model that focuses on maximizing profits for shareholders. A model that drives inequality at home and keeps workers in developing countries destitute as Western companies export labour to where it is cheapest, forcing foreign governments to keep wages low or lose business. In other words, no more jobs for us, and perpetual poverty for them.

Incidentally, this global economic model is also driving climate change, with global trade estimated to outpace global growth over coming years, meaning emissions from global freight are set to skyrocket from 2.1 billion tonnes per year in 2010 to 8.1 billion by 2050.

The shipping industry is a real stinger, too, as while its accounts for 940 million tonnes of Co2, or 2.5 per cent of all carbon emissions per year (the same as Germany) as no country technically owns these emissions, they don’t fall under reduction targets. And so they get to go on unabated. As a side note, this is why buying local produce and avoiding fast fashion is so important.

Redirecting the money

So far, so gloomy; but what’s the answer? Despite the resounding failure of revolution over the past few hundred years, many would still argue that the overthrow of the capitalist regime is the only way forward. Your writer, however, would argue that perhaps a better way to change a capitalist system is to change the way the capital flows around it.

Very few of us feel in anyway part of global markets: seeing our small bank accounts as entirely divorced from the excesses of Threadneedle or Wall Street. However, this couldn’t be further from the truth. All of us, no matter how small our money, play a role. The cash in our current account gets invested by the banks, as do our pension savings, and right now most of us have no say, and are making no profit from that – because most of us don’t even know.

In 2010, an Australian lung cancer specialist named Bronwyn King found out that – like 99 per cent of pension savers on the planet – her retirement savings were funding Phillip Morris, Imperial Tobacco and other peddler’s of cancer. Shocked, she embarked on a nationwide campaign to raise awareness and pressure pension funds to divest from tobacco. To date, more than 35 have now done so. In the UK, Nest is the only national pension fund to pledge to quit the cigs.

And it’s not just tobacco, folks. Through our bank accounts and pensions we are funding fossil fuel, arms, mining, big pharma, big banks, big tech: you name it. If you don’t engage with your cash, someone else will, and usually by putting it in areas you would likely bend over backwards to avoid in your everyday life.

This is not just a moral question: it’s a financial one. By keeping savings in cash and default funds we are missing out on returns in areas like renewable energy and clean technology that could not only be saving the planet, but our pockets too (check out our regular top performing sustainable fund series for a flavour). In a new world where fossil fuels are being regulated out of existence, the smart money has already moved and we’re all being left behind.

The answer to global inequality and political instability, then, is a type of revolution – just not the usual. Imagine, instead, that tomorrow every single one of us took our pension savings out of the default funds full of fossil fuel and tobacco and put them instead in a sustainable investment fund through a self invested personal pension? These industries would collapse overnight. And this is no exaggeration.

The answer, then, is a mass shareholder revolution. What are we waiting for?